Identity can be expressed through many mediums and based upon various aspects of the self. Race, gender, and class are common bases for identity. However, people also use other aspects of life to help define who they are. Identity can even be based off of commercial products. Take, for example, the way people dress. Most people choose their clothes to fit within their perceptions of themselves. As a result, when people shop, they buy products that reflect their identities. For our research project, we decided to look at how the products we shop for online are representative of our identities. How do the products we consume represent who we are? How do online retailers, like Amazon, learn about our identities through what we buy, and how do they use that information to appeal to us via advertising? What are the implications of seeing personally tailored ads online when we consider those ads as an interpretation of one’s identity?

To answer these questions, we researched the topics of identity through commerce and conducted a personal experiment. We began our research by examining the link between consumption and identity. We then focused on the specific examples of the Deadhead fans of the Grateful Dead and Nike products in Honduras. We also considered scholarship on how advertisers use knowledge about consumers’ identities to sell their products. For our experiment, we looked specifically at Amazon, the most popular online shopping site and a major advertiser on the Internet. We investigated whether ads shown by Amazon accurately reflect identity and how those ads could impact the viewer. Our analysis of our experiment’s findings draws on our research to consider how the Internet and the algorithms that track our spending habits affect the interactions between consumption and identity. Our analysis tries to illustrate what the link between consumption and identity looks like in the Internet age.

Our research on the interaction between consumption and identity included various articles that were all built on the assumption that the products we buy have meaning. Commodities have meanings attached to them. These meanings can be obvious – for example, the way that a Baltimore Ravens jersey means that the wearer is a football fan – or more subtle. As consumers, we use the meanings attached to products to reflect and strengthen our beliefs about ourselves, infer things about others, and identify ourselves as belonging to certain social groups. One way that consumers use commodities to define themselves and belong to a group is through consuming music.

Music, as a good produced by an industry, falls under the category of processed and profitable sources of identity. Many people use the music they listen to as an expression of who they are. In this way, music can form communities, strengthening that identity as the listener becomes not only a fan of an artist but a member of a larger group. This is because certain types of music are often associated with certain views and standards. As a result, many avid fans of a band are likely to share not only their musical interest, but their opinions on larger topics as well.

One prominent example where people connected through music was the “Deadhead” community of Grateful Dead fans. Politically charged lyrics combined with a sound appealing to people with those views and as a result followers of the Grateful Dead were like-minded people. The band formed such a popular touring act because of their very dedicated fan base. In turn, the fans felt that going to shows and being a Deadhead was an integral part of who they were. Here, commercial products, albums and concert tickets, are being purchased by people in order to realize their identity as fans. However, identity based on possessions and experiences created by other people may not be able to endure. When band member Jerry Garcia died, this community was in upheaval. How could these people go on living their lives as Deadheads without the band? Some members remained active in the Deadhead community, supporting the remaining members’ subsequent projects in order to hold on to this part of themselves. However, there were also people who left the community, who removed this part of themselves.

In the same way that consuming Grateful Dead music identified Deadheads with certain political views, our research about consumption and identity found that some products have complex political meanings attached to them. For example, the Garifuna, a community of black Hondurans, identify Nike brand products with similarly complex political meanings. Beginning in the 1980s, Nike advertisements associated Nike products with African American athletes and an image of masculinity linked with a kind of “inner city authenticity” (Tsing 165). Nike’s interpretation of black masculinity resonated with the Garifuna, who use Nike’s logo and products as a symbol for empowerment and economic success. Anthropologist Mark Anderson writes that ‘‘Among Garifuna in Honduras, the Nike swoosh circulated as a polyphonic icon of youth resistance, racial blackness, economic status and corporate power’’ (Tsing 165). The power of the Nike swoosh as a symbol can be seen in its use in varied contexts: Garifuna painted the symbol on the sides of taxis, houses, and even on rocks, and some tattooed it on to their bodies or shaved it into their hair. The Garifuna’s use of Nike products to represent a part of their identities is an example of how the goods we consume reflect and reinforce the ways we see ourselves.

The Deadheads and Garifuna might be considered what Sarah Banet-Weiser calls “consumer citizens” in her book Authentic TM. Consumer citizenship means expressing ideas about politics and identity through consumption. Banet-Weiser’s scholarship on consumption and identity points out an important component of the interaction between the two: the fact that brands and businesses are aware of consumers’ use of their products to express their identities and use that knowledge for profit. Brands sometimes choose to appeal to consumers’ identities and political views by using social activism as a means to advertise. An advertising campaign that uses social activism to sell products is called “commodity activism” (Banet-Weiser 16). A prominent example of commodity activism is Dove’s Campaign for Real Beauty, which uses ideas from the feminist and body positive movements to sell Dove products. When we shop online, we interact with more than just advertising campaigns like these that may or may not be tailored to our viewpoints. We also see content generated by algorithms whose job it is to show us products that appeal to us. These algorithms’ ability to personally tailor our experience with advertisements means that brands and advertisers could use the interplay consumption and identity for profit more powerfully than ever before.

During our personal experiment part of the research process, we looked into how online shopping, particularly on Amazon, influences the ads shown to you on the Internet. We wanted to know how these ads reflected the identity of the user. We hypothesized that at the end of the experiment, the ads would form a fairly complete picture of the other user. For our experiment, we would trade computers for ten minutes every day for three days. During that time, we would search for products we found related to us. Then, in our daily Internet usage, we would screenshot any Amazon ads we saw. It was easy to ensure that no one else would be disturbed by our experiment; we would be the only ones to see the advertisements.

While we had expected the ads to show us many different items related to the items we had viewed, we found that Amazon almost exclusively showed us ads of the exact products we had previously clicked on. This has led us to conclude that Amazon does not try to assume what we would and would not like, it simply regurgitates our shopping history back to us. It was also interesting how quickly the new periods of searching changed the ads we were shown. After each period of searching, the ads of products the other person had just searched for replaced the ads of products from the search before. The result of this was that we not shown anything near a generalization of the things the other person was interested in. We saw nothing more than their most recent searches.

Our experiment found that Amazon’s algorithms are not sophisticated enough to make judgments about a user’s identity through the goods they consume, at least not to the point that Amazon can recommend new products to the user that appeal to their sense of self. We proved Amazon searches are not a definitive picture of someone’s identity, despite attempts by advertisers to gather information this way. But even though Amazon’s advertising capabilities have not yet progressed to that level, the ads Amazon shows us are still very relevant to our identities. When we went online and the ads tried to sell us products that we had already expressed interest in by clicking on them in Amazon, that was an algorithm used to determine who we were and what we might purchase. These ads show us the same products over and over again because it has been concluded that if you already viewed those products, you are more likely to buy them. Being shown the same ads repeatedly reinforces an online consumer’s identity. The idea that seeing advertisements for the same products strengthens our view of ourselves is similar to Eli Pariser’s concept of filter bubbles that we discussed in this class. We are being shown identical products over and over instead of a representation of all of the products on Amazon. This means that Internet ads are repeatedly reinforcing a constructed interpretation of the user’s identity. As time goes on and the user is bombarded with these types of ads, they may come to believe in that identity.

All in all, our project sought to understand how the Internet and algorithms that track consumer behavior might strengthen the relationship between consumption and identity. From the limited findings of our personal experiment with Amazon advertisements, we believe that Internet algorithms have not yet progressed to a point where they are able to get a clear picture of a consumer’s identity and tailor the individual consumer’s online experience accordingly. However, a broader experiment might find that Amazon’s algorithms are more sophisticated than they have been in our experience. Whether through advertising filter bubbles or through more complexly constructed advertisements geared towards an individual’s identity, the Internet is causing the relationship between consumption and identity to evolve.

SCREENSHOTS

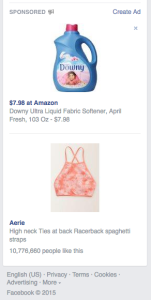

The search history on the left shows Chris’ searches for laundry detergent and fabric softener. On the right, Amazon showed Emma an ad through Facebook for the exact fabric softener that Chris had searched for.

The search history on the left shows Chris’ searches for laundry detergent and fabric softener. On the right, Amazon showed Emma an ad through Facebook for the exact fabric softener that Chris had searched for.

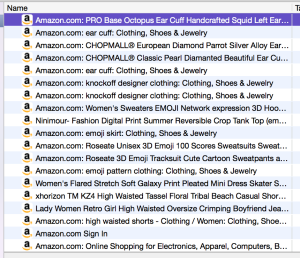

Emma’s browsing history on the left contains all three of the items pictured above in an ad on AZ Lyrics.

Works Cited

Banet-Weiser, Sarah. Authentic ™: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. NYU Press, 2012. Print.

Duffett, Mark. Popular Music Fandom: Identities, Roles and Practices. New York: Routledge, 2014. Print.

Pariser, Eli. Beware Online “Filter Bubbles.” TED. Mar. 2011. Web. http://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_filter_bubbles?language=en

Tsing, Anna. Supply Chains and the Human Condition. Rethinking Marxism: A Journal of Economics, Culture & Society. London: Routledge, 2013. Print.

Zimmerman, Ian. We Are What We Consume. Psychology Today. New York: Sussex Publishers, LLC, 2013. Web.